Health Blindness

See our TED talk on Health Blindness

What Does It Mean To Be Health-Blind?

While there are countless electronic medical sensing tools, at the end of the day medical personnel still rely on their naked-eye visual skills when examining and judging the medical signs and health of patients.

On that note approximately 5% of medical personnel – 10% of men and 1% of women – are “health blind”, which means they are severely perceptually handicapped at sensing the health signs of patients. More often than not, the medical personnel and those that hire them don’t even realize they are health blind.

So who are these “health blind” medical personnel?

The short answer is any medical professional that is color blind is considered to health blind since it has long been documented that red-green color-deficients are disabled at seeing veins, vasculature, pallor, cyanosis, jaundice, rashes, bruising, erythema, retinal damage, ear and throat inflammation, and blood in excretions. Even 18th-century scientist John Dalton, who was color blind, observed that he “could scarcely distinguish mud from blood.”

Considering that even today 10% of the 500 most prevalent medical conditions list skin color changes amongst the signs to look for, individuals that are red-green color deficient are unable to distinguish reds and greens, which make them unable to see everyday health color signals on the skin.

Color deficiency can consequently lead to medical misdiagnosis and has at various times prevented entry into medical school.

So... If you’re red-green colorblind, then you’re health-blind. In that thread, if you’re mildly color deficient, then you are also mildly health-blind.

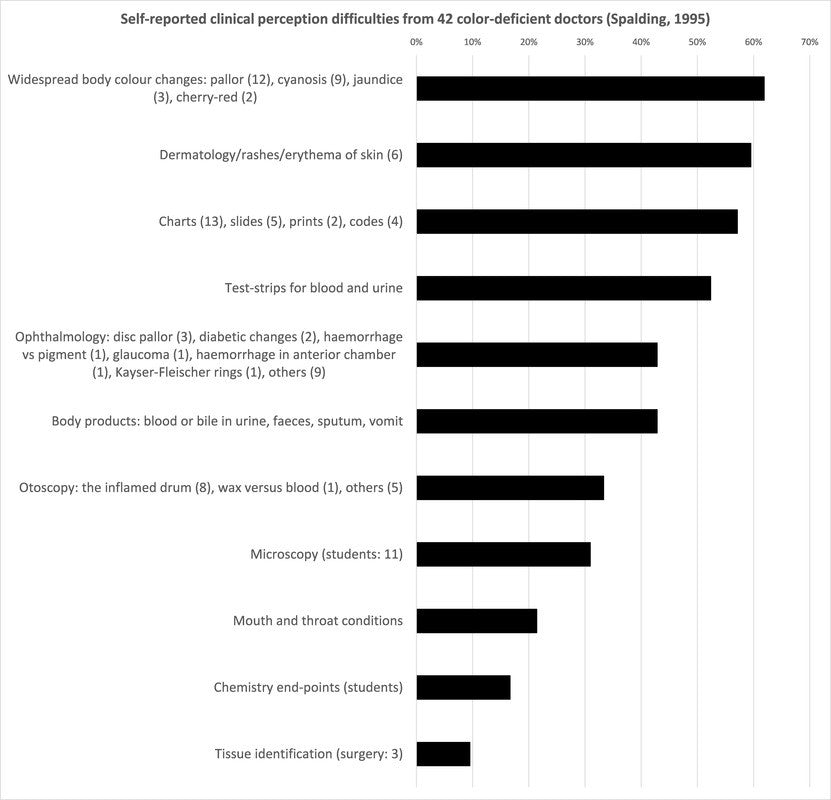

The graph below shows the reported clinical difficulties among 42 color-deficient doctors surveyed by Spalding (1995). NOTE: Keep in mind that this particular graph shows reported difficulties, and thus doesn’t capture what the color-deficient doctors don’t realize they’re missing.

A variety of occupations (e.g., pilots, police) routinely require passing a color exam before entry, and in some countries passing a color exam is even required in order to get a driver’s license.

But, except in rare instances (e.g., Hiroshi, 1998), color blindness has not been a formal barrier for becoming a physician.

Unfortunately, a recent discovery by researchers at our 2ai Labs shows that color blindness is not just a problem for medical personnel, but a disproportionate problem for the medical community.

In 2006, we showed that color vision evolved specifically to distinguish health and emotion states on the skin: our peculiar primate variety of color vision evolved to be optimized for sensing the oxygenation modulations hemoglobin undergoes under the skin (Changizi et al., 2006).

Red-green color vision is uniquely about seeing oxygenation, and therefore red-green color-deficients are especially hindered at seeing the skin signals that underlie health signals. Unlike other fields where colorblindness is a handicap but where it is actually fairly unlikely to find perfectly

Unlike other fields where colorblindness is a handicap but where it is actually fairly unlikely to find perfectly indiscriminable colors to a color-deficient, the oxygenation variations of blood under the skin are completely invisible to the red-green colorblind because they’re missing the evolved machinery specifically designed to detect it.

This makes color blindness a critical issue in clinical settings for patient health. Approximately 5% of clinical personnel are handicapped at detecting everyday health signals on the skin including seeing veins, and yet many are not even aware of their handicap. On that note neither are the many other personnel who are only mildly color-deficient (sometimes due to aging).Color deficiency is also a serious liability issue for medical staff and their employers, and color deficient doctors have been sued on this basis (see

Color deficiency is also a serious liability issue for medical staff and their employers, and color deficient doctors have been sued on this basis (see citation to News & Observer).

The O2Amp Medical Solution for Color-Deficiency

Historically there has been no solution for the color deficient clinician. Varieties of filtered eyewear for color deficients exist that can help them pass Ishihara tests or perceive certain discriminations among objects in the world. But none were designed to enhance the signal that primate color vision evolved to detect: oxygenation variations in the skin (Changizi et al., 2006). And thus no previous color blindness treatment was consistent with the health perception demands of medical personnel.

We at 2ai Labs, having discovered the evolutionary function of color vision, were in the unique position to design optical technology to enhance the signal for which color-deficients are deficient. In particular, we created O2Amp, our company highlighting several distinct optical technologies for enhancing perception of facets of the blood under the skin.

For color deficients our flagship technology is our Oxy-Iso Color Blind Correction Medical Eyewear, designed to amplify and isolate the oxygenation signal coming from under the skin. Color-normals use the eyewear to enhance perception of veins, but color-deficient medical personnel use the eyewear to amplify their minimal baseline sensitivity to oxygenation variations in the skin.

The Oxy-Iso doesn’t merely aid color deficiency…

…the Oxy-Iso aids color-deficiency in a manner consistent with the medical-sign-, vasculature-, and health-perceptual needs of doctors, nurses and other medical personnel.

REFERENCES

-

Ahlenstiel H (1951) Red-green blindness as a personal experience. Kodak Research Library, London.

-

Anthony J, Spalding, B (1999) Colour vision deficiency in the medical profession. Br J Gen Pract 49: 469-475.

-

Anthony J, Spalding B (2004) Confessions of a colour blind physician. Clin Exp Opt 87: 344-349.

-

Best, F, Haenel H (1880) Rotgrün blindheit nach schneeblendung. Kin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. Beilagen 45: 88-105.

-

Campbell JL, Spalding AJ, Mir FA, Birch J (1999) Doctors and the assessment of clinical photographs—does colour blindness matter? Br J Gen Pract 49: 459-461.

-

Campbell JL, Spalding AJ, Mir FA (2004) The description of physical signs of illness in photographs by physicians with abnormal colour vision. Clin Exp Optom 87: 334-338.

-

Campbell JL, Griffin L, Spalding AJ, Mir FA (2005) The effect of abnormal colour vision on the ability to identify and outline coloured clinical signs and to count stained bacilli in sputum. Clin Exp Optom 88: 376-381.

-

Changizi MA, Zhang Q, Shimojo S (2006) Bare skin, blood, and the evolution of primate color vision. Biology Letters 2: 217-221.

-

Changizi MA, Rio K (2009) Harnessing color vision for visual oximetry in central cyanosis. Medical Hypotheses 74: 87-91.

-

Cockburn DM (2004) Confessions of a colour blind optometrist. Clin Exp Opt 87: 350-352.

-

Cole BL (2004) The handicap of abnormal colour vision. Clin Exp Opt 87: 258-275.

-

Currier JD (1994) A two and a half colour rainbow. Arch Neurol 51: 1090-1092.

-

Dalton J (1798) Extraordinary facts relating to the vision of colours. Memoirs of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society 5: 28-45.

-

Hiroshi T (1998) Relaxation of university admission restriction for students with abnormal color vision. Japan Ophthalm 59: 123.

-

Jeffries BJ (1983) Colour blindness—its dangers and detection. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA.

-

Little WS (1881) Experience of a red-blind physician with one ophthalmoscope. Practical advantage of colour-blindness with a case. Arch Ophthalm 10: 20-22.

-

Logan JS (1977) The disability in so-called red-green blindness. An account based on many years of self-observation. Ulster Med J 46: 41-45.

-

News & Observer. Partially blind, color blind surgeon continues to practice despite lawsuits.

-

Reiss MJ, Labowitz DA, Forman S, Wormser GP (2001) Impact of color blindness on recognition of blood in body fluids. Arch Int Med 161: 461-465.

-

Savin JA, Hunter JAA, Hepburn NC (1997) Skin Signs in Clinical Medicine. Mosby-Wolfe, London.

-

Spalding JAB (1993) The doctor with an inherited defect of colour vision: the effect on clinical skills. Br J Gen Pract 43: 32-33.

-

Spalding JAB (1995) Doctors with inherited colour vision deficiency: their difficulties in clinical work, In Cavonius CR. Ed. Proceedings of the International Research Group for Colour Vision Deficiency. Kluwer International Publishing: 483-489.

-

Spalding JAB (1997) Doctor with inherited colour vision deficiency: their difficulties with clinical work. In Colour Vision Deficiencies XIII (ed. Cavonius, C.R.) Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 483-489.

-

Spalding JAB (1999) Medical students and congenital colour vision deficiency: unnoticed problems and the cases for screening. Occup Med 49: 247-252.

-

Spalding JAB (2004) Confessions of a colour blind physician. Clin Exp Optom. 87: 344-349.

-

Spalding A, Cole B, Mir F (2012)

-

Steward SM, Cole BL (1989) What do colour vision defectives say about everyday tasks? Optom Vis Sci 66, 288-295.

-

Voke J (1980) Colour vision testing in specific industries and professions. Keller, London.

-

Wilson G (1855) Research on colour blindness with a supplement. Southerland and Knox, Edinburgh.